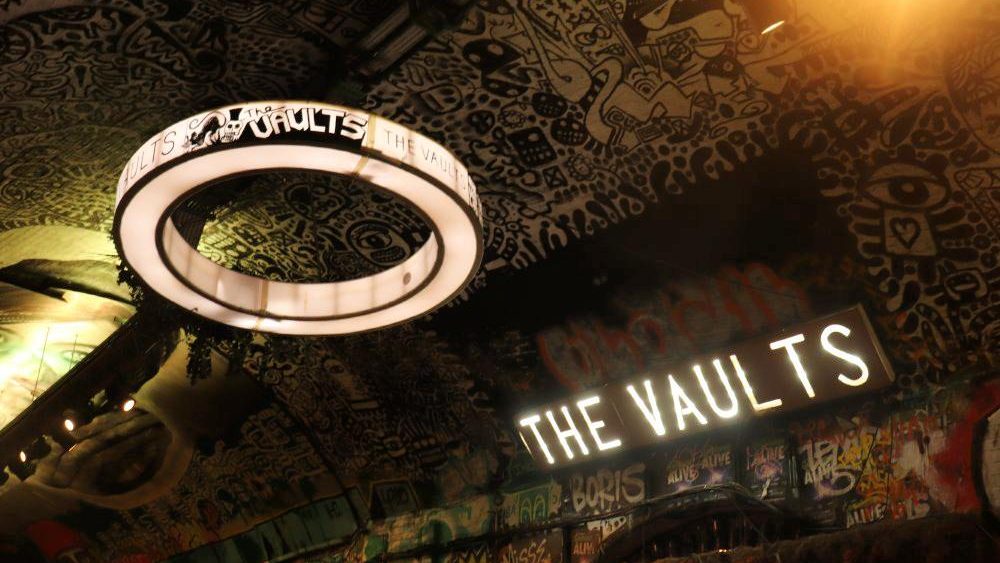

It is never nice to hear a much-loved arts events is closing for good – but it’s less nice still when it comes out of the blue. There was the bombshell news last year that the owners of the space underneath Waterloo station didn’t want them back again, and the immediate worry was over money. Then the concerns of money grew quieter and focus turned to finding the right replacement venue. A replacement was found. The Vault Festival took on new branding, #SaveVault became #BuildVault, and a big relauch gala was supposed to take place at the end of this month. Surely this was proof more than anything that Vault Festival was home and dry?

But Vault Festival was not home and dry after all. It turned out the original issue of money was their final downfall after all. We don’t know the details, but based on their statement, it looks like it came down one particular funding application that they’d assumed they were going to get. Unfortunately, all of the other funding they were counting on was dependent on this one, and without that, the whole plan fell apart. All relaunch activities are cancelled, the newly-secured space isn’t going ahead, and most of all of the year-round staff are being made redundant. Reading between the lines in this article, it seems that they maybe hadn’t exhausted all options, but they’d run out of energy and are giving up. It’s not completely the end of the enterprise – the year-round space The Glitch that they ran next to the main space is still going ahead, but that’s all. If somebody does managed to rebuild the Vault Festival or something like it, it will have to be good as starting from scratch.

I am going to refrain from commenting too much about London theatre. From my point of view, the Vault Festival was good for being the closest thing you’ll get to a fringe, but that’s a minority pursuit – most performers and regulars see Vault as important component of the London Fringe Theatre scene. The Vault may not run year-round, but London Fringe performances do. One problem frequently highlighted with small-scale London theatre is cost. The costs of Edinburgh Fringe as well known, but even hire of similar-sized venues in Greater London have a reputation for being costly. The Vault was said by some to be a better route in to theatre – but without much familiarity of London Theatre myself, I’ll stop there and let others go over that.

So how has something that looked so promising only days ago gone so wrong so quickly? The main answer lies somewhere in the balance sheets, and with neither access to the books nor much experience of how financing of large venues work, there’s not much I can say about that. But off-hand, I can think of a lot of things that went wrong for the Vault Festival. Most of them were outside their control and staggeringly unfair – but some problems they maybe could have avoided.

5 problems the Vault Festival didn’t deserve …

So, what went wrong that was outside their control? Here is my list.

1: Arts funding in general

Yes, I know, it’s a very obvious point. We can debate arts funding till the cows come home. We can argue over spending and taxation in general, and we can also argue over whether – if cuts must go ahead – the arts are getting more or less of their fair share in cuts. But there can be little doubt it’s made survival a lot harder. Obviously you’re less likely to get a venue-saving public grant if there’s less money to go round. But it’s not just that. Had the same thing happened to the Vault Festival in pre-austerity days – losing a venue and failure to secure a key grant – there’s a good chance the rest of the arts community would have clubbed together to save it. That’s much less likely to happen if all the other organisations are also struggling to save themselves.

By far the biggest problem and the most obvious problem. But I think there are other structural problems in the arts that has hit Vault hard.

2: Landlords are cocks

It’s not the first time I’ve said this, and it probably won’t be the last. The only reason we have the successful upstart Laurels in the north-east is because Theatre N16 was driven out of London by landlord cockery. But it seems we have all have underestimated the scale of the problem. When Vault got cancelled in 2022 – and you have my permission to add this to your list of “Times when Chris Neville-Smith was confidently wrong” – I said the one advantage they had was that there wasn’t any threat to the venue. It’s not like anybody’s going to want to convert a dank space underneath Waterloo station into a Wetherspoons.

However, it turns out More Sodding Chain Pubs wasn’t the only threat. It appears that the Vaults Theatre (the year-round leaseholder of the space) wanted Vault Festival out to make way for more lucrative immersive theatre pieces. From a purely commercial point of view, I think that’s insane. The Vault Festival was a reliable money-earner, and immersive theatre deal is not – and if you must explore that route, surely the sensible thing to do would be to do this in April-December to start with. Well, whatever the Vault Theatre was expecting, it didn’t happen. They’ve also scared off all of their other hires. There is nothing at all announced foo 2024. Unfortunately, just because I was right and the Vault Theatre was wrong, it doesn’t undo anything. Everybody loses. It might be a deterrent if future cockish landlords think twice before pulling a stunt that reckless. But it’s little consolation to the Vault Festival, because the damage is already done.

I really hope it’s a wake-up call of just how big a menace this is to the arts. It takes years to build up the communities surrounding these arts venues, only for the work to be destroyed in an instant for short-term landlord gain. Landlords might argue they’re just running a business, but the arts world let the Vault Festival down very badly by not recognising the value of places. Probably little hope with this government, but the next government needs to be lobbied hard on the long-term value of arts premises – even if this comes at the expense of running costs for arts organisations. I will soon write up my proposal for how I think this should work – I can only hope the downfall of the Vault Festival is not a lesson wasted.

3: Lack of support from London

If there’s one thing where I feel the arts community let Vault down, it’s their tendency to blame the most convenient targets and not necessarily the right targets. The easy punching bag is “bastard cuts from bastard Tories”. But whilst a lot of blame can be attributed to this, they’re not entirely responsible. Much as I appreciate the importance of Vault to London artists, it is really a London matter, and there’s a well-resourced Mayor of London to take care of London matters. The Vault Festival is just as important to grass-roots performing arts in London as the Edinburgh Fringe is to the UK – and even the Tories aren’t wouldn’t let the Edinburgh Fringe go bust on its watch.

So why isn’t the Mayor of London up in arms about this? Or the Deputy Mayor for Culture? Or anybody on the Greater London Assembly? The North of Tyne Mayoralty has just found £523,000 for a new venue – upscale that for London and you’re looking at £5 million or more. Surely that would be enough to save Vault Festival? Now, I’m not saying North of Tyne was right and London was wrong – I’m aware of grumblings over favouritism over here, maybe London does things by the book. But to not even say anything at all? The cynic in me wonders if the Mayorlality would rather be quiet and let the Vault Festival die, than say something and face questions for why they’re not helping.

But never mind why Sadiq and co aren’t up in arms about this – why aren’t we up in arms that Sadiq and co aren’t up in arms? Do we suddenly forget our mantra to fund the arts when it makes our political soulmates look bad? I never expected much from this government, but I thought we’d get better from the Mayor of London. If the people with the purse-strings get a free pass just because we like their politics, we really are in trouble.

4: The “count your chickens before they’re hatched” culture

If I was going to comment on finances, I might question the wisdom of allowing so much to hinge on a single funding application. In particular: was it a good idea to recruit staff without knowing if you had the money for them? And then there’s the question over going for such an ambitious year-round venture? If it had come off, all these risky decisions would have been vindicated and the threat of getting kicked out by a landlord would be gone for good. But it didn’t, and at the risk of sounding like Captain Hindsight, one must ask if would have been wiser to seek something less ambitious but more reliable.

However, there is one point to be made in defence the reckless practice of planning major spending without the funding: it’s normal. And the way arts works, it’s difficult to run any other way. We’ve just had chaos from the latest round of NPO applications. The arts organisations who lost funding had only a few months to adjust, and in many cases had to cancel things they’d already programmed on the assumption they were getting the money. Even small-scale arts applications are frequently required to book a venue first and apply after – you have to cancel if you don’t get it. And, worse, nobody seems to think this is a problem.

Based on that, I can easily see why Vault Festival had not option but to choose a grand plan A with no plan B. Who knows, if we had a culture didn’t force you to count your chickens before they’d hatched, we might have had a plan B. Perhaps carrying on with the loose network of venues used for a Pinch of Vault. This plan B would have been a big step backward and a big shrinkage of the Vault Festival. But it’s better than no festival at all.

5: The “Edinburgh or bust” mindset

I know, I’m using an event to push something I already believe, but I’m sure most fans of the Vault Festival would agree that it’s unhealthy to treat Edinburgh Fringe as the only way to get noticed. Lots of artists risk more than they can comfortably afford to lose at Edinburgh because they think they have no other option. Now, if Edinburgh Fringe was one of several viable options, demand for Edinburgh would reduce and costs would rebalance to something sane. But most of the arts industry have been digging their heels in and refused to consider talent from anywhere else.

What is most frustrating is that the Vault Festival was having more success than anyone is being taken seriously as an alternative to Edinburgh. But sadly this wasn’t enough. Now, if Edinburgh Fringe itself had recognised that they are at their strongest as part of a festival circuit, the might have realised how much the Vault Fesitval was an asset to them. There might have been a bigger push to do something.

Unfortunately, this means Edinburgh Fringe’s demand is going to be pushed up and made more expensive. And this couldn’t have come at a worse moment for anybody.

… and 3 mistakes Vault might have made

Although the Vault Festival had everything stacked against them, I do think they made a few errors of judgement. As I said, I’ll refrain from commenting on their funding strategy, because that all seems to happen behind closed doors and I don’t know what happened. But there are some things more out in the open.

1: Lack of contingency planning

Okay, I made exactly the same mistake – but that’s exactly why you should take nothing for granted. I assumed the Vault Theatre would never stop hiring their space to the Vault Festival because they’d never make more money doing anything else – but the Vault Theatre evicted them anyway.

Let what happened to Vault be a warning to all other businesses dependent on a single partner. It could be a landlord, it could be a long-time collaborator, it could be a steady funding stream, it could be an online platform, or many other things, but the effect is the same: your partner can turn on you without warning. Always have a plan ready against the disaster scenario. You might have to downsize your operations for a while and rebuild, but it’s better closing completely.

There is a similar concept in the public sector called “Business continuity”. There’s a team who try to anticipate everything that could go wrong, and prepare for all of them. What if your main office burns down tomorrow? Can you switch to working from home? Can you get alternative premises? Should you have places ready on standby? And so on. Now, of course, the Vault did have a plan, but that was created after the bombshell news. Was judgement clouded too much by wanting proving your old venue wrong? Would a pre-prepared plan have been less dramatic but safer? We will never know – but the more prepared you are for these disasters, the better.

2: The cancelled 2022 festival

Who knows, maybe a pre-prepared contingency plan would have been no better than the plan they put together. However, at the risk of sounding like Captain Hindsight, I really think they made a big error of judgement with the Vault 2022 festival. It’s not fair to say that Vault Festival ignored the risk of Covid in 2022 – they did work this in as a contingency plan, with social distancing on standby in the event this was necessary. As we all know now, this wasn’t enough. Could we have reasonably foreseen the chaos that Omicron would spread? Perhaps not.

But you don’t need to be a microbiologist to know that a winter festival was always going to be the riskiest time to put on a major event. Especially one set in crowded underground rooms. There was no certainty at the time that any other date would be safe – even a festival starting in the summer might get cancelled if a variant came at the wrong moment. But past experience told us winter was the biggest risk – and had they from the outset scheduled Vault 2022 to start in, say, March instead of January, things would probably have been okay. Unfortunately, past experience tells us that the worst possible time to cancel a festival is just before it starts: all of the upfront expenditure, none of the income. This hit Brighton Fringe in 2020, and they reportedly would have gone to the were were it not for the Pebble Trust bailout – but Brighton Fringe was hit out of the blue; Vault Festival knew what they were dealing with.

I did wonder whether the 2022 crisis would cause enough of a financial crisis to derail the 2023 festival. It didn’t – but perhaps it deprived them of the reserves needed to survive the 2023 crisis. Maybe it didn’t matter, maybe they had good cancellation insurance, but if I could turn the clocks back and change one decision, it would have been the timing of Vault 2022.

3: Over-dependence on one selling point

No, I’m not going to get into that binfire of an argument right now, but the Vault festival makes a big deal of how much of their programme is from women and minorities. Their selection process almost certainly favours some groups over others. All I will say for now is that this was a key reason why the Vault Festival was set up. It’s their festival, and I respect their decision to run it how they choose.

But when it came to saving their festival, I think they made a tactical error by choosing this as their selling point, ahead of everything else. When they started in 2012, there were few organisations pushing for greater diversity in the arts. Now, however, it’s practically impossible to operate subsidised theatre without major moves towards a diverse programme. As a result, what was once a unique selling point is now quite ordinary. Worst of all, if this is your way of attracting funding, you’re competing with dozens of other organisations offering similar things.

My hunch is that it would have been a better bet to focus on affordability to artists. I’m no expert on London, but that seems to be the thing that the rest of London fringe theatre is consistently bad at – and judging from the response to the closure of Vault, this was the most valued thing about the Vault Festival. Any funding body can point to dozens of other organisations in London making the arts more diverse – but can they say the same about affordability? This is only speculation – just because the plan that was tried didn’t work doesn’t mean the plan they didn’t try try would have worked better – but it’s still my hunch. We will never know who was right.

And finally, two wild suggestions …

I don’t know what’s next for fringe-level theatre in London. The factors that counted against Vault Festival so heavily are pretty much the same factors elsewhere. There’s no immediate prospect of better arts funding nationally, London-based funding doesn’t seem much better, and so far nobody seems to be willing to take on the problem of short-term landlord greed. In spite of this, these are the areas where efforts have to be made. If none of these improve, I can’t see any chance of things getting better.

However, here’s a couple of outlier ideas. One of these is a long shot – the other idea is very painful but maybe necessary.

1: Time for peace talks between Vault Festival and Vault Theatre?

I know the Vault Theatre have justifiably made themselves into the number one hate figure here – but since nobody’s won and everybody’s lost, this might be an opportunity. Rebuilding relations would, of course, require an enormous amount of pride-swallowing on both sides. The Vault Theatre would have to admit that its grand immersive theatre ambitions were a pipe dream. The Vault Festival would have to abandon their once-triumphalist stance that they never have to do business with those greedy landlords again. Such a decision might make business sense for the Vault Theatre, although it’s maybe not so attractive for Vault Festival. If your landlord turned on you once, might they turn on you again?

In practice, it’s more likely to be a variant of this. Maybe it might be a new group of creatives, taking inspiration from the Vault Festival but having no affiliation themselves. (If, as I suspect, there was a rift between Vault Theatre and Vault Festival we don’t know about, this would be one less barrier.) Or maybe the current leaseholder will abandon the space and a new leaseholder will see the value in a winter festival like Vault did. It’s not impossible for the Vault Festival to end up moving back into their original space under a new leaseholder. A very long shot, but stranger things have happened.

Alternatively:

2: Time for small theatre to abandon London?

There is a radically different way of looking at this. For decades, the expectation has been that you have to go to London to make it. And there has been some truth to that. London reputedly has a much better progression route from zero to serious professional. Much of the arts media pays more attention to theatre productions with a London run. But might this all be a self-perpetuating cycle? The arts media pays attention to London because that’s where the stuff worth seeing is, but is the stuff worth seeing going there because that’s where the arts media pays attention? Anyway, this worked a lot better when London was affordable. It’s not just the arts where costs are spiralling away – everything in London is spiralling away … Maybe, just maybe, the solution is to give up on London and regroup somewhere else.

The obvious alternative is Manchester. This has a network of small theatres comparable to London, but without the stupid price tags that come with the capital. It wouldn’t be too difficult to have some sort of focused festival – maybe a souped up version of the existed Greater Manchester Fringe, maybe a curated festival in a single location. London theatre has done rather well from the TV studios around – actors will frequently do a London Fringe play in gaps between filming – but Manchester could easy overtake London there. Media coverage is only a problem as long as the media choose to make it a problem. And yeah, the ousting of London as the place to be will be a big loss to London creatives, but London’s loss is the north’s gain. As for the rest of us – if I must risk it all and move to seek my fame and fortune, give me Manchester over London any day. I don’t have a trust fund.

This idea will probably go down like a lead balloon in London. But, ultimately, what happens to London is in the hands of London. Vault Festival has almost certainly closed not because the London Mayorality couldn’t come to the rescue, but because it wouldn’t come to the rescue. At the moment, all of the effort is going into high-end cultural attractions such as the West End. But the West End does little for small-time creatives finding their own voice – it was organisations like the Vault that did this, and now that’s gone. London collectively has to make a choice: do they value grass-roots culture or not? Because they ca’t take it for granted any more. They’ve just lost one of their greatest assets at the grass roots without so much as a shrug from the people meant to nurture this. London, whether you go on to lose the rest of this is up to you.