Firstly apologies for this article being late. I do appreciate being invited to season launches and aim to give coverage as swiftly as possible, but the unfortunate news about the Vault Festival took precedence. But now there is time to catch up.

Just a reminder before we start that this is not a comprehensive guide to everything covered at the launch – I leave that up to other media outlets. My interest is more with what grabs my attention. Much of this comes down to whims; something the doesn’t get my attention can turn out to be a gem – and very occasionally, something I was convinced was a surefire hit is a let-down. My final of what’s worth watching is always after this has come and gone.

That caveat established, let’s go. There are aspects of all three main plays that grab my attention, then I’ll move on to some other highlights. One unusual observation: after a crowded autumn/winter 2023, there’s a big gap in main stage productions until May 2024, with the three main plays scheduled between then and March 2025. I’m a bit surprised they’ve picked May over March, because the conventional wisdom’s always been that the colder months (except January) tend to sell better than warmer months. Not reading anything into that: just a curiosity.

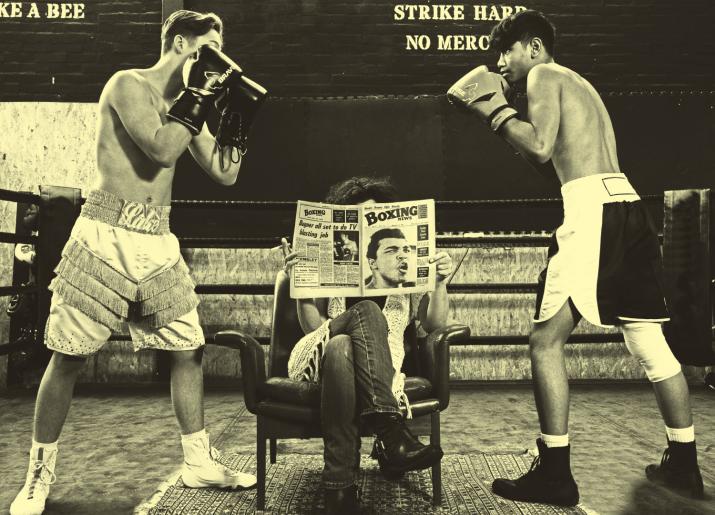

Now, out of the three main plays, my hot bet is Champion by Ishy Din. He is one of the writers I have the most respect for, and in my opinion, his previous Live play Approaching Empty was very under-rated. Although he predominantly writes characters of Asian descent, the themes are almost always universal and could just as easily be anybody’s story. I was particularly impressed with the characterisation. In a story where everybody uses and betrays those closest to them, you always – with the exception of one character who’s a hardened criminal – understand why each of them felt they were doing the right thing. I also credit him with giving some of the best advice to aspiring writers: in particular, he has spoken a lot of sense about the “big breakthrough” myth which far too much of the new writing ecosystem still subscribes do. Anyway, the subject of the new play? The visit of Mohammed Ali in 1977 to South Shields, although there’s hints that the real subject of the play is a mixed-race family living in South Shields at the time.

Continue reading

With the stage set around a pool table, there’s a couple of of signs to show it’s the nineties: a payphone by the wall, and £1.50 for a pint of beer (I said as I stared longingly). Len (David Nellist) and Michael (Dean Bone) are playing pool taunting each other on their respective football affiliations of Newcastle and Sunderland and/or resolving confusion over what you now call the Second Division. Until Michael drops in a downer by mentioning that a mutual friend of theirs has unexpectedly died. However, whilst Michael is reflecting on their loss, Len is keeping his eye on the bigger picture. That unfortunate guy was the local MP, and Len’s convinced he’ll be a shoo-in as successor, much to the annoyance of Jean (Jessica Johnson), who’d rather have a husband there for her. Unluckily for Len, Victoria (Eve Tucker) from Manchester is also eyeing up the seat – and, worse for him, already seems to have the backing of Labour’s NEC.

With the stage set around a pool table, there’s a couple of of signs to show it’s the nineties: a payphone by the wall, and £1.50 for a pint of beer (I said as I stared longingly). Len (David Nellist) and Michael (Dean Bone) are playing pool taunting each other on their respective football affiliations of Newcastle and Sunderland and/or resolving confusion over what you now call the Second Division. Until Michael drops in a downer by mentioning that a mutual friend of theirs has unexpectedly died. However, whilst Michael is reflecting on their loss, Len is keeping his eye on the bigger picture. That unfortunate guy was the local MP, and Len’s convinced he’ll be a shoo-in as successor, much to the annoyance of Jean (Jessica Johnson), who’d rather have a husband there for her. Unluckily for Len, Victoria (Eve Tucker) from Manchester is also eyeing up the seat – and, worse for him, already seems to have the backing of Labour’s NEC. But, in spite of the very strong competition, there could only be one winner, and that is Samuel Bailey with

But, in spite of the very strong competition, there could only be one winner, and that is Samuel Bailey with

First, a lesson in recent local history. I must confess, I had no idea Durham Prison was such a controversial subject. The last I heard, it was a prison with reluctant guests included Myra Hindley and Rosemary West. When it came to public attention there was a high rate of suicide, the high-security women’s wing was closed it it became a men-only prison. One might have thought the authorities would have also actually tried to stop the stupidly high suicide rate – instead, it appears they just shrugged. Usual word of caution for any creative writing based on a true story: there is little to stop a theatre depicting a one-sided account without allowing those under fire their side of the story. However, Ric Renton’s account is consistent with the publicly available information about Durham Prison – and considering that this prison has recently been changed completely from a category A Prison to a reception prison – I suspect those in charge of the prison today will accept this was fair.

First, a lesson in recent local history. I must confess, I had no idea Durham Prison was such a controversial subject. The last I heard, it was a prison with reluctant guests included Myra Hindley and Rosemary West. When it came to public attention there was a high rate of suicide, the high-security women’s wing was closed it it became a men-only prison. One might have thought the authorities would have also actually tried to stop the stupidly high suicide rate – instead, it appears they just shrugged. Usual word of caution for any creative writing based on a true story: there is little to stop a theatre depicting a one-sided account without allowing those under fire their side of the story. However, Ric Renton’s account is consistent with the publicly available information about Durham Prison – and considering that this prison has recently been changed completely from a category A Prison to a reception prison – I suspect those in charge of the prison today will accept this was fair.

I confess, I missed Shelagh Stephenson’s A Northern Odyssey the first time round. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, this was before I’d got familiar with works such as The Memory of Water and Five Kinds of Silence and realised how good a writer she was – and secondly, this was at a time when I was being deluged with identi-kit “local” plays with the laziest of north-east references. However, this one went down very well and I wished I had caught it. So I was keen to take the opportunity to catch up on this, but also see what the People’s Theatre can do with this.

I confess, I missed Shelagh Stephenson’s A Northern Odyssey the first time round. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, this was before I’d got familiar with works such as The Memory of Water and Five Kinds of Silence and realised how good a writer she was – and secondly, this was at a time when I was being deluged with identi-kit “local” plays with the laziest of north-east references. However, this one went down very well and I wished I had caught it. So I was keen to take the opportunity to catch up on this, but also see what the People’s Theatre can do with this.